“Can I get you guys a little warm-up?”

The words make me feel like I’m home, even though I’m 200 miles from it. That Midwestern spark in her voice, the way she cares about serving an outsider from two states over just as much as her own.

The coffee pot hovers over my half-empty mug. I nod. Of course.

A local at the next table asks another how it’s going.

“Oh, ya know, just out here trying to survive.”

Not your standard Midwestern ‘Not too bad,’ but close enough.

Aren’t we all just trying to survive, buddy? Trying to outrun the demons of our minds and the bill collectors stuffing our physical and digital inboxes?

Across the street, a woman sweeps between the front of a hair salon and the American Legion. The concrete beneath her broom is surprisingly pristine—a town cared for meticulously, even as the rest of rural America crumbles.

Redfield, South Dakota, looks like something out of Field of Dreams, like that moonlit Main Street where Ray Kinsella walks and talks with Archie Graham.

It’s weird how quickly a place can feel like yours. Like you’ve been here forever, even if it’s just one stop on a long road.

A place that feels frozen in time, stubbornly hanging on.

And speaking of stubborn—let me tell you about John.

The man eats like nothing I’ve ever seen before. They didn’t give him the high school nickname ‘Hotdish Mountain’ for nothing.

Except … nobody called him that in high school. It’s just some shit I made up because it should have been his nickname. Figure if I repeat it enough, maybe it’ll stick.

But trust me—the name fits.

Full sleeve of Oreos? Gone.

Double quarter-pounder with cheese and 20 McNuggets? Get outta here.

Better add two slices of French toast with caramel sauce for good measure.

The man defies human biology. No weight gain. No bloating. Every meal punches its own EZ-Pass and cruises straight through his digestive system without slowing down.

A couple hours earlier in Chamberlain, Hotdish Mountain wasn’t pleased when we skipped breakfast.

We had a choice:

1. Turn back into town and find something greasy.

2. Put the GMC into the wind and hope to run into something later.

We took our chances.

The road stretched out in front of us, endless and empty—the kind of drive where the only landmarks are grain elevators and the occasional roadkill. My stomach grumbled. I was starting to feel it, too. Two hours later, still nothing.

Typical South Dakota things. You can drive a hundred miles in this state without seeing a town, a rest stop, or a human being.

Breakfast? Even rarer.

Then, up ahead—Leo’s Good Food. A main-street corner diner, the kind of place that just feels right.

Maybe it was the name—Leo, same as my daughter’s basset hound, a real freak of a thing. Hyperactive, with ears four times bigger than they should be, always dragging through his water bowl and leaving a trail of soggy disaster everywhere he goes. More character in that floppy little bastard than in most towns I’ve passed through.

Didn’t even need to check Google reviews—Leo’s had that same unshakable certainty as a dog with ears too big for his head.

You just know it’s good.

The wind tunneled through Main Street as we crossed.

Inside, it was a full-blown time warp. The place wrapped you up in an embrace that only 1976 could understand.

Brown leather booths, worn smooth from decades of conversation. A section of tables with matching chairs, backs creased from years of leaning. Square-patterned western wallpaper that somehow just worked—framed waterfowl prints, shelves cluttered with knickknacks.

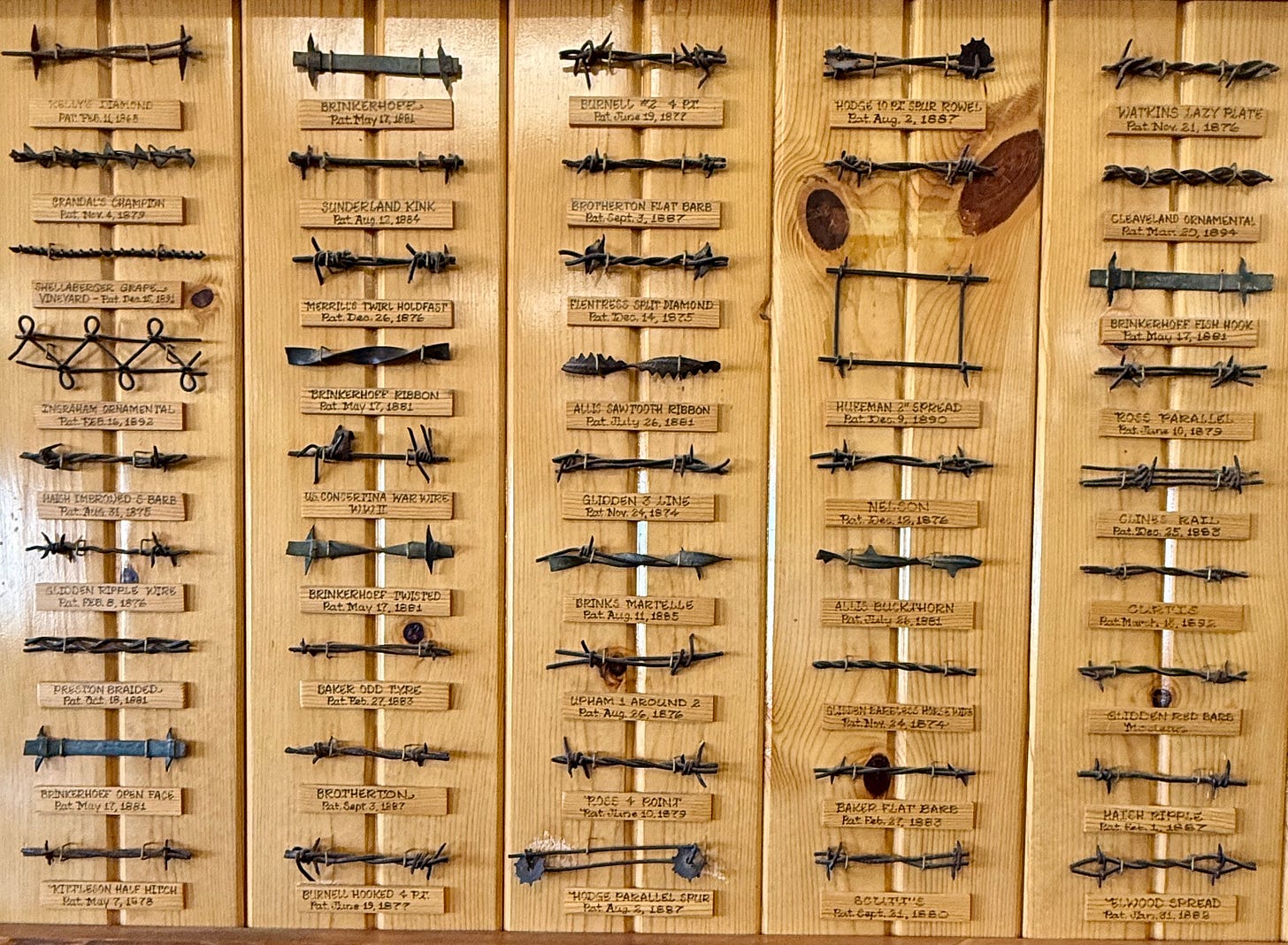

And the barbed wire. A full-on diagram, forty different kinds, framed like someone thought it deserved museum status.

Not decorated so much as accumulated—the physical manifestation of a community’s shared history.

“Hey, Hotdish, what do they call those banister things over there?”

“Hell if I know,” he said. “You mean the ones every kid gets his head stuck in?”

Yeah. Those. That makes sense.

While I was jotting notes, Hotdish was locked in on a refrigerator full of pies behind the booth.

I heard him chuckle. A low, sinister “hu hu … huh huh huhhhhh” like an alcoholic preacher sneaking a nip before barreling into Sunday’s sermon.

Across from us, a man sat down at the short bar. Dead ringer for Harry Caray. Or at least the Will Ferrell version of Harry Caray from Saturday Night Live. I imagined him saying: “Cubs win! Cubs win! It’s all Budweiser and stadium hot dogs on the road to the American dream!”

And just as I was settling into the comfort of absurdity, the moment changed.

A waitress visited with a young woman at the counter.

“We always knew you’d make it through,” she said.

They hugged. The girl walked out the door.

A minute later, our waitress came back to the table.

“Served that girl most of her life. She had stage four cancer,” she said, pointing to her forehead—brain cancer.

But she made it. And she made it back here.

Brave soul. Such a trooper.

And suddenly—my eggs taste better. The words slipped out before I could stop them.

For the rest of breakfast, Hotdish and I hardly said a word.

The yolks were yellower—almost orange—the way eggs used to look before industrial farming took over. The hash browns had that perfect contrast between the crispy, lacy edges and the tender middle that only comes from a well-seasoned flattop that's seen decades of service. The coffee had that particular diner smoothness that no fancy pour-over can replicate—a Lutheran-approved blend—the flavor of community more than beans.

Appreciation takes over. For health. For life. For the chance to be here.

Some things won’t last, but that doesn’t make them any less worth savoring.

Helen. I think I’ll call her Helen.

I forgot to ask her name. But I’ll remember her face—the soft lines of someone who’s spent years caring for other people, the kind of presence that makes you feel like she’s known you forever, even though you just met.

Helen wasn’t always slinging coffee and warm-ups. Back in 2005, she was crunching numbers for British Petroleum, right before they decided to drag accounting into the modern age.

Before that, she had done everything by hand—pencil, paper, physical spreadsheets. The kind where every number mattered because there was no software safety net to catch mistakes.

BP assumed technology would replace her methods, but Helen had other ideas. She figured out how to use Excel not as a replacement but as a verification system. She did the math by hand—the way she trusted—then used Excel as a second opinion.

Months later, the company held a contest: pass an Excel proficiency audit, get a $500 bonus.

When her supervisor checked her work, Helen’s screen was blank—no digits, no spreadsheets. But beside her sat every calculation, handwritten and dead accurate. More accurate than anyone else's. She nabbed the bonus without ever fully adapting to the digital world.

The company told her technology would make life easier. But Helen liked the hard work—liked knowing exactly how she arrived at every number.

People like Helen don’t resist change because they’re stuck in the past. They resist it because they know not everything newer is better. Maybe that’s why places like Leo’s still exist, too—some things are worth doing the hard way.

Like everything we’ve watched disappear over the last forty years, time has already set its sights on Leo’s.

Since 2019, America has lost over a quarter of its independent restaurants and diners—nearly 90,000 local establishments gone for good, according to the National Restaurant Association.

It won’t be long before Leo’s is just another boarded-up storefront, another Main Street story sealed in plywood and left to fade into history.

The pie refrigerator? Gone.

The leather booths? Auctioned off to the highest Facebook Marketplace bidder.

Another small-town café lost—not because people didn’t love it, but because not enough people loved it enough to keep it alive. Memories, boarded up. Replaced by chain restaurants with stainless steel walls and prison aesthetics.

Because we keep choosing convenience over connection.

And yet—I don’t leave Leo’s feeling hollow.

The door jingles behind us as we step outside. There’s sadness, sure. But also appreciation. Gratitude for these few minutes. This moment in time.

This memory? It’s mine.

The warmth. The connection. The realization.

It’s all so damned special. And I’m learning to be okay with it.

Okay with knowing you can’t hold onto everything forever. That places like Leo’s won’t last, no matter how much we wish they would.

History isn’t ours to keep—it’s only ours to witness.

And that makes it matter more.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Like those leather booths at Leo’s, some things need time to break in. But I’ve been trying to wear this pamphlet out instead.

So I’m stepping back—three days, three weeks, however long it takes. The rhythm will change, but the voice won’t.

For those who’ve paid to support this work, I get it—this might not be what you signed up for. But I hope you’ll stick around. What comes next will be worth the wait—just like those hash browns at Leo’s.

take care! I enjoy your column, this one was especially good, reminded me of where I grew up and places I'd gone with my dad

Oh Man! This is the kind of storytelling that makes you feel the impermanence of your high school stairwells and the many things that happened there, and realize that you never grasped what you had until you didn't. It's like listening to the music of the past even as your dreams steep you in the future.

But this piece is also a moment of prescient warning...

What will we lose if we don't take care to preserve it? What do those losses mean?

And then, we'll be wondering around like a body, lost in a blizzard, wondering how to make it back to the only home we ever knew.

The suffering of lost connection is so real and so visceral in your pieces Adam. Thank you for writing. 🙏